Australia and Germany have a letter of co-operation in place for the export of more than 100 Boxer vehicles – one of Australia’s largest military export deals (Australian Defence Department)

SYDNEY — Australia’s new export regime, a mix of new laws and policies meant to extend the country’s ability to share technology with the US, UK and other close partners, should directly lead $600 million AUD in foreign sales over the next decade, while increasing the number of international researchers the Lucky Country can engage with.

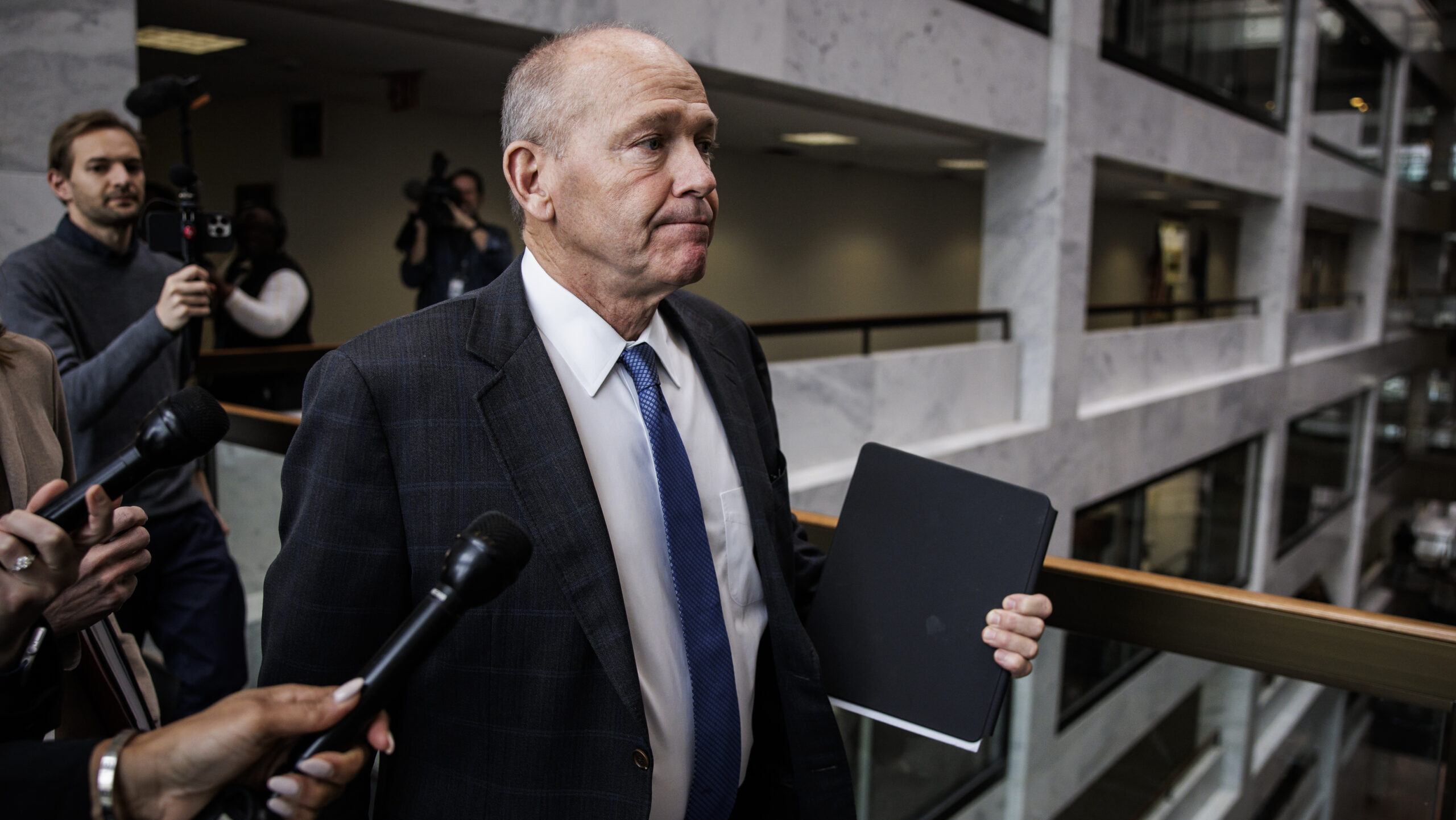

That’s the claim Hugh Jeffrey, Australia’s deputy secretary of strategy, policy, and industry made during a Canberra speech sponsored by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington-based think tank.

“The reforms will deliver, in our judgment…a net decrease in regulatory compliance costs, and actually expand the amount of research that can occur internationally without a permit,” Jeffrey said today. “This in turn is expected to generate a net benefit to the Australian economy of over $600 million over the decade and, with the national exemption for export permits from the US and UK, remove regulation from $5 billion of almost $9 billion in annual Australian defense exports.

“So, I hope I’ve convinced you that there’s some really significant generational change taking place, but it’s not a silver bullet.”

The reforms introduced in mid-November came under sharp criticism from some experts and organizations. The president of the Australian Academy of Sciences, Chennupati Jagadish, was not optimistic. “My ability to attract the best and brightest in the world, wherever they are, will diminish,” he said at the time. “It’s timely to ask what Australia is really seeking to secure if we are restricting the development of technologies that are critical for the future of our country?”

Bill Greenwalt, who as a staffer on the Senate Armed Services Committee wrote many of the US export control rules, said he thought “Australia just gave up its sovereignty and got nothing for it.” Greenwalt, also a former US deputy undersecretary of Defense for industrial policy, warned that incorporating many of the principles of the International Trafficking in Arms Exports (ITAR) regulations to gain access to US nuclear submarine technology would set Australia back 50 years.

Jeffrey conceded critics like Greenwalt had made their points, but he offered that the Group of Eight, a university consortium, the Australian Industry and Defense Network, which represents industry, and the Tech Council of Australia, a lobby group for the industry, “support the bill and the approach that we’re adopting.”

He described that approach as striving “to strike a balance between facilitating increased international collaboration and national security requirements.”

He told the trans-Pacific audience that “the bill will not prevent foreign nationals from working with Australia on goods or technology controlled on the defensive strategic goods list. It will not prevent foreign students or academics from engaging with Australian academic institutions.

The bill, he insisted, “is designed to prevent sensitive defense goods and technologies being passed to foreign actors in a manner that may harm Australia’s interests. And this expanded Export Control Framework will not prevent trade, but some activities may require a permit prior to these activities occurring, as many defense trade activities do now. So, think scalpel, not sledgehammer.”

Why are these changes needed? Is it only to more closely bind Australia to the United States and Britain in return for access to the technology and intellectual property that comes with the primary goal of the AUKUS agreement — buying and building nuclear-powered attack submarines?

The Second Offset strategy’s technologies, pursued by the United States in its effort to overtake the Soviet Union, were guarded by the ITAR restrictions. The advanced technology that gave what Jeffries described as “an unrivaled technological superiority” was restricted largely to the US. “But almost all those seminal technologies have now proliferated. And in some instances, Russia and China are outpacing the US and its allies in terms of capability in some areas,” he said. “So the point is, a run-faster strategy alone, is not going to work. We need to run far faster, but that won’t avail us if we just try to do it alone.”

The three allies of AUKUS are responding. He said the 2024 National Defense Authorization Act, passed by Congress, “represents I think the biggest reform to export controls in decades.” But to make the system work well “the defense trade controls amendment bill now before (Australia’s) Parliament will form a key piece of our ability to move more closely and integrate with our partners on the defense industrial base.”