Mark Cancian, a member of the Breaking Defense Board of Contributors, is a retired Marine colonel now with the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Speaker of the House Mike Johnson (R-LA) is joined by Rep. Elise Stefanik (R-NY) and Rep. Cory Mills (R-FL) for a news conference on November 07, 2023 in Washington, DC. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

In the wake of the Oct. 7 attack on Israel and Russia’s continued war in Ukraine, the Biden administration is seeking to pass $106 billion in extra funds — but it’s not going well in Congress. In this new analysis, Mark Cancian of CSIS breaks down the requested funding in two different ways, in order to provide greater insight to the Hill as negotiations continue.

On Aug. 10, the Biden administration requested $40 billion, $24 billion of which was for Ukraine, enough to get through the period of a continuing resolution. However, that request went nowhere. On Oct. 20, the administration expanded this request to $106 billion to cover a full year of aid to Ukraine as well as border security, support to Israel, and military enhancements.

So far, all approaches for enacting a bill have failed. Earlier this month, House Republicans responded by passing a bill funding aid to Israel by cutting funds for the IRS and deferring the rest until later. However, the White House threatens a veto, and the Senate will not even consider the bill. The Senate, including Republicans, is willing to fund the entire package and is considering legislation to do that. However, the Constitution requires that appropriations arise in the House, so the Senate cannot drive the process. Its leadership fumes on the sidelines.

It seems clear that getting the entire package passed as is won’t happen. As a result, the best way ahead might be to put aside the all-or-nothing approach employed so far and examine the aid package, piece by piece, from different perspectives. There are two ways of doing that: categorizing by purpose and categorizing by immediacy.

Thinking about this funding in different ways could help Congress reach a consensus about what to fund immediately, what to push into the regular budget cycle, and what to drop entirely.

Categorization 1: Divide By Purpose

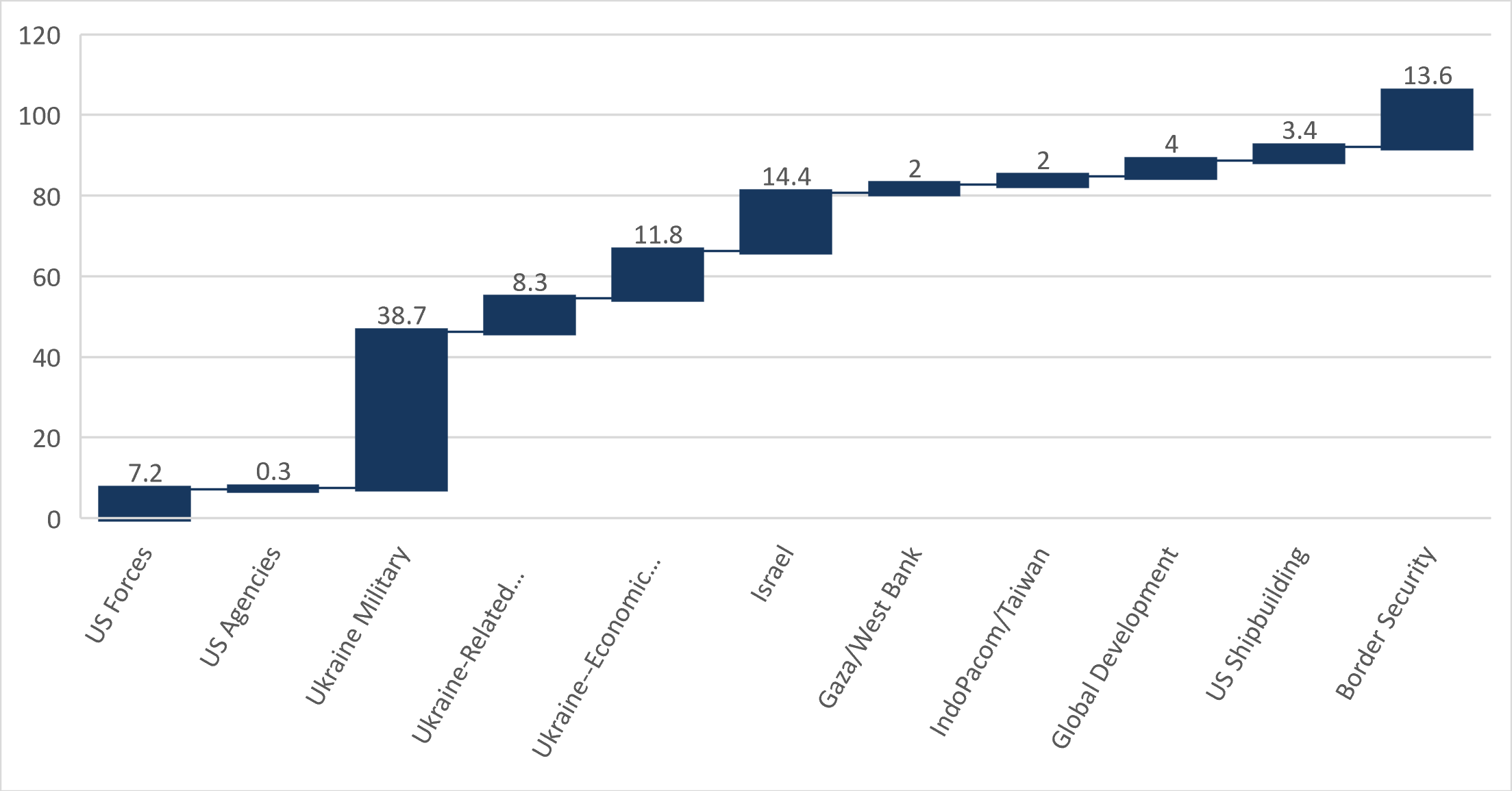

The first categorization would be by purpose. The chart below shows the $106 billion supplemental divided into eight separate pots:

A description of each purpose follows. By considering the funding’s purpose, Congress might judge that some items do not meet the “emergency and unexpected” standard set by OMB for items to be included in a supplemental, or that some items need a more thorough understanding before proceeding.

US forces ($7.2 billion): Pays for the continuing US troop surge to Europe made at the beginning of the Ukraine war to reassure our allies and deter further Russian aggression. Although the number of reinforcing troops is down to about 10,000, their deployment generates costs that were not included in the original FY24 budget. Funds would go mostly to the Army, with some Navy and elements of the other services also funded. The request also includes $609 million for strengthening cyber security of US forces in Europe.

US agencies other than Defense and State ($285 million): Funds the National Nuclear Security Administration for non-proliferation and protection in Ukraine in case of a nuclear event. Also contains some funding for enhanced Department of State activities, including $15 million for Inspector General oversight.

Ukraine-related military aid ($38.7 billion): Funds provision of equipment to Ukraine as well as support services such as intelligence. Most of this aid comes from two sources: $12 billion for the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative (USAI) and $18 billion for replacement of equipment sent to Ukraine and reimbursement for services provided by the United States. The purposes for which this $30 billion can be spent are broad: “training, equipment, weapons support, supplies and services, salaries and stipends, sustainment and intelligence support.”

Ukraine-related humanitarian aid ($8.3 billion): The largest piece is for disaster relief and economic development in Ukraine ($5 billion). Another element is for Ukrainian refugees in Europe ($2.5 billion) and in the United States ($481 million); the final element covers counternarcotics operations related to the war ($360 million).

Economic support to Ukraine ($11.8 billion): Provides money to the Ukrainian government to replace lost tax revenue so it can sustain basic governmental services.

Support to Israel ($14.4 billion): Nearly all military. Replaces US equipment sent to Israel, supports development of “Iron Beam,” a laser version of Iron Dome, procures more missiles for Iron Dome and David’s Sling, provides $3.5 billion for additional military procurement, and expands US munitions and weapons production ($1 billion).

Humanitarian aid to Gaza/West Bank ($2.0 billion): The administration is explicit about this need. The White House veto statement on the House funding bill states, “Humanitarian aid is critically needed to alleviate the suffering of civilians in Gaza.” The amount is an estimate because this aid is an element of two broadly described aid efforts that also cover Ukraine and global needs.

INDOPACOM/Taiwan ($2 billion): Provides financing for weapons and munitions, understood to be mostly for Taiwan, but phrased so it could go to any ally or partner in the region.

US shipbuilding ($3.4 billion): Upgrades public and private shipyards so they can reduce maintenance backlogs, better sustain the fleet, and increase shipbuilding production rates, especially for submarines.

Global economic development and disaster relief ($4 billion): Funds USAID and the World Bank to counter the Chinese belt and road initiative, strengthen economies in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, and help “the poorest countries respond to severe crises.”

Border security ($13.6 billion): Covers wide variety of border and migrant activities such as additional agents and migrant handling. Includes $100 million for enforcement of child labor laws.

Categorization 2: Near-term Vs Long-Term Needs

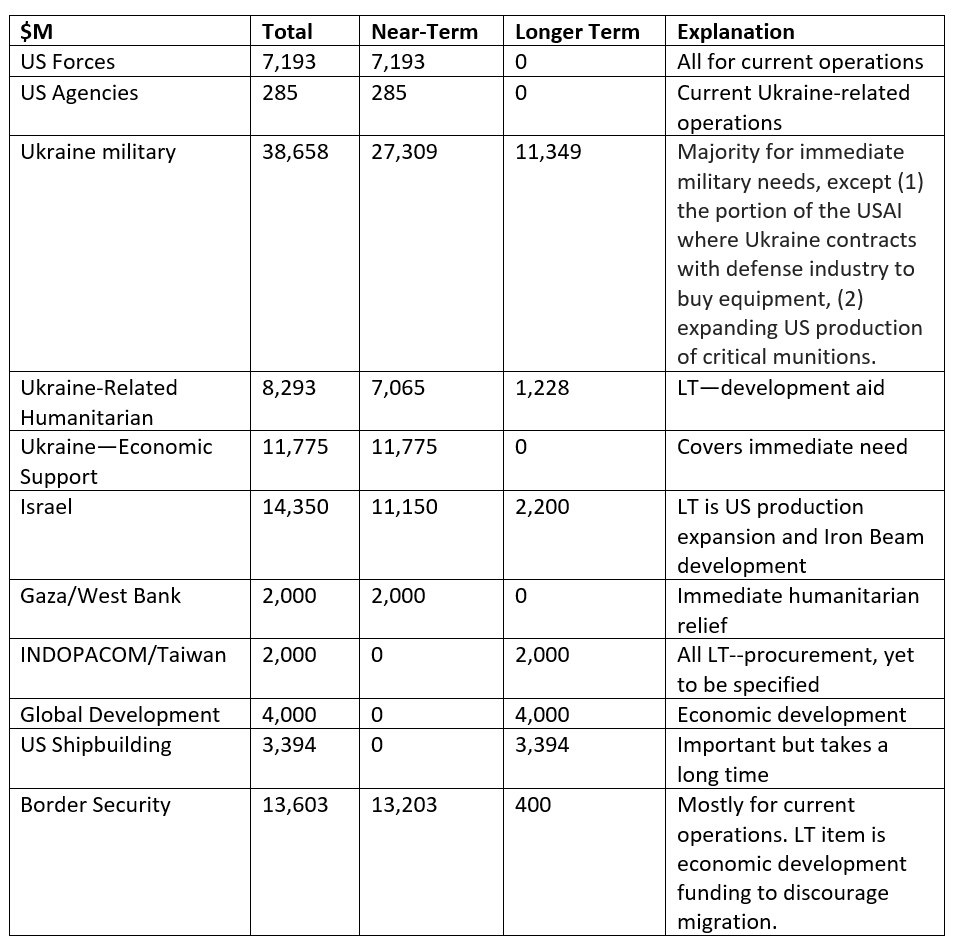

Another perspective is the immediacy need — how much is needed this year and how much is needed longer term.

Near-term is defined here as money needed within FY24. It includes funds for military operations, humanitarian assistance, and economic support. Longer-term is money that could be postponed, if necessary. This category includes funds for weapons production (except replacement of drawdown) because the timelines for producing such equipment run two to three years, industrial base enhancement (a well-documented need but with a long timeline), and economic development efforts (which are inherently long term). The analysis thus identifies items that should go into a supplemental based on immediacy and items that could go through the regular budget process — i.e., inclusion in the regular FY24 appropriation or deferral to FY25 — to allow time for analysis and discussion.

This is not a question of needed versus unneeded. Many of the items in the longer-term category are critically important — for example, expansion of munitions production, procurement of new weapons and enhancements to US shipyards. It is solely a question of timing.

The table below shows the balance between near-term (76 percent) and longer-term needs (24 percent).

A table of spending figures in the near- and longer-term, provided by the author. (Mark Cancian)

Looking Forward To Next Steps

Looking at the supplemental from both a purpose and timing perspective gives members of Congress a way to put together a package that is acceptable to many, if loved by few — the definition of compromise on the Hill.

It’s also worth noting that deficit hawks might want to save their fire for the next battle. The OMB director’s letter to the House Speaker stated, “I anticipate submitting a request for [additional] supplemental funds … required to address recent national disasters, avoid the risk that millions of Americans lose access to affordable high speed Internet or childcare, provide additional resources for the Federal Emergency Management agencies nonprofit security grant program, avert a funding cliff for wildland firefighter pay … and [fund] the special supplemental nutrition program for women infants and children.”

One can argue whether that forthcoming supplemental contains good ideas, but the items represent major policy choices that Congress should debate. Except for natural disasters, these are likely not “emergency and unforeseen” and might be pushed to the regular budget process.

Congressional dysfunction has become a standing joke on the comedy circuit. While Americans have always enjoyed ridiculing their government in Washington, it is irresponsible to let a $5 trillion federal government and the most powerful military in the world drift. To govern is to choose. It’s time for Congress to make choices on this supplemental.