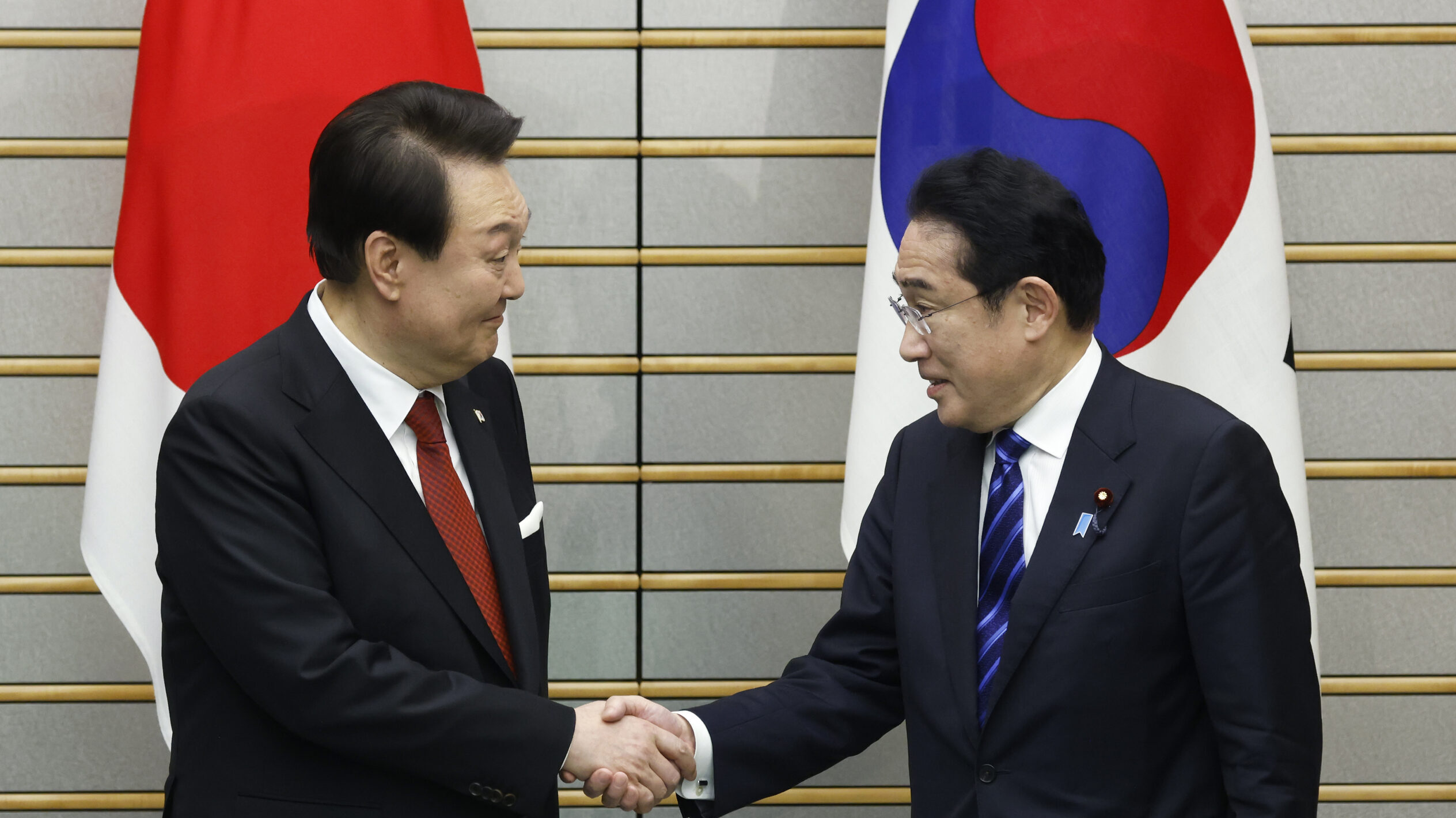

Yoon Suk Yeol, South Korea’s president, left, and Fumio Kishida, Japan’s prime minister, shake hands ahead of a summit meeting at the prime minister’s official residence on March 16, in Tokyo. (Photo by Kiyoshi Ota – Pool/Getty Images)

Updated 4/17/23 at 1:54 pm ET to clarify the status of GSOMIA after 2019.

SYDNEY — North Korea’s barrage of missile tests and China’s swelling military modernization appear to have driven two of Asia’s reluctant partners back into each others arms, with South Korea and Japan agreeing to restore the sharing of highly classified intelligence.

South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida met during March 16 in Japan, and shortly thereafter South Korea announced it was resuming the use of the General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA). A deal signed in 2016 after pressure on both sides from the US, GSOMIA designed to share information between Tokyo and Seoul on North Korea. Under the original terms of the deal, Japan would send satellite imagery and electronic information to South Korean analysts, who reciprocate with human intelligence going back to Japan.

Getting the deal signed was a big win for the Obama administration, but a trade dispute and continuing tensions over the comfort women issue led South Korea to pause participation in the deal in 2019. At least, the trade dispute was the nominal reason: Relations between the two countries have been rocky for decades. Japan, Korea’s former colonial master, has never directly apologized for its behavior during World War II, and the issue of so-called comfort women, Koreans forced to sleep with Japanese soldiers, still resonates.

Since then, the governments in both countries have shifted, and in 2022 officials made clear there was interest in resuming GSOMIA. Following the March summit, Yoon announced plans to “normalize” the agreement going forward.

North Korea offered a reminder Thursday of the perils its neighbors face, when it tested its first ICBM in a month, a test that was soundly condemned by the White House, even if it serves as a sign for why GSOMIA is important.

“Japan and South Korea need real-time information sharing to improve operational readiness to defend against North Korean missiles,” Patrick Cronin, the Asia-Pacific security chair at the Hudson Institute in Washington, wrote in email.

“The restoration of the bilateral GSOMIA and the desire now to expand intelligence and other types of security cooperation are made possible by President Yoon’s determination to improve relations and Japan’s growing anxiety about an assertive China,” Cronin added.

While Yoon may be more willing to work relations with Japan than his predecessor, the pact still faces the fundamental issues that have caused its fragility, argued Frank Aum, an expert on northeast Asia at the congressionally-funded US Institute for Peace in Washington.

“For decades, both countries have recognized the need to settle past historical issues from the Japanese colonial period and improve their diplomatic and economic ties in order to address common challenges,” Aum said in a commentary published by the institute.

“However, past agreements meant to resolve their differences, such as the 1965 normalization treaty and claims agreement and the 2015 comfort women agreement, were often vague or paid insufficient attention to victims’ concerns for the sake of political expediency and national goals. These agreements allowed the two countries to improve relations sufficiently enough to achieve gains in security, development and prosperity,” he continued. “But because they didn’t resolve fundamental questions about the colonial period, the agreements remained controversial — subject to different interpretations and recurring risks of collapse.”

While GSOMIA”s resumption is good news for proponents of regional intel sharing, the US may have a growing headache in how it relates to South Korea in the form of the massive military intelligence leak that has dominated news cycles this month. While Yoon has downplayed the documents revelations about US eavesdropping on high-level South Korean decision makers, there are growing criticisms coming from the public and political opposition.

“The leaked US documents are a reminder that in our digital world the mass unveiling of secrets is an ever-present threat. AUKUS proceeds knowing that the most important secrets should only be entrusted to those sharing security interests and common values,” Cronin wrote, referring to the US-UK-Australian deal. “Five Eyes and Japan and South Korea do share most interests and values. Even so, security should be shared also on a need to know basis to protect the system that makes the cooperation useful.

“The bottom line is that the exposure of US classified material will slow but not stop allied intelligence sharing. Part of intel sharing is having clear ground rules on intelligence collection and dissemination, and these issues will no doubt be revisited more assiduously.”