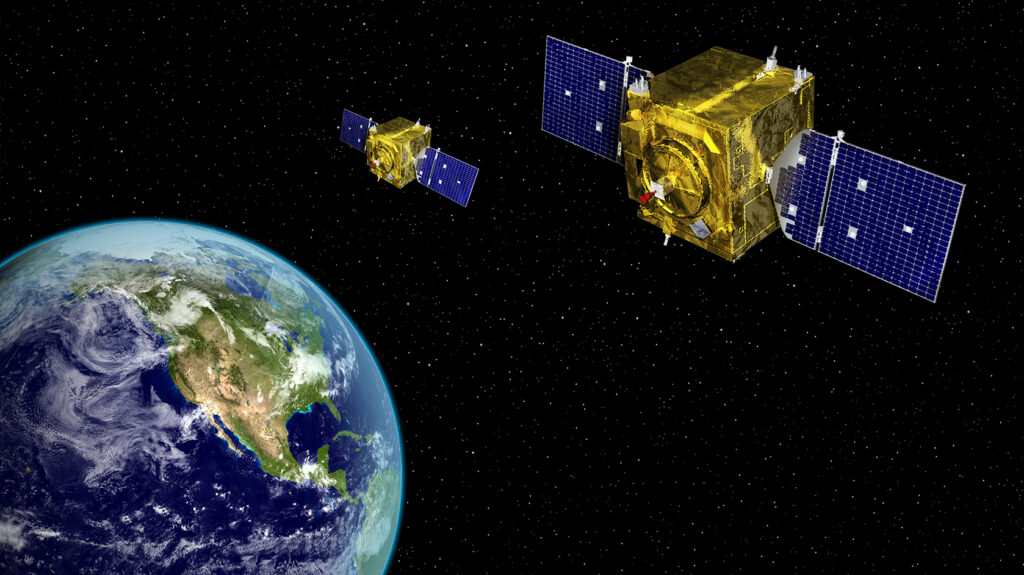

Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Program ‘neighborhood watch’ satellites (Air Force Space Command archives)

WASHINGTON — US Space Command’s urgent requirement for “coherent battle management” capabilities and modern, computerized decision-making tools to keep real-time eyes on objects in orbit remains unfilled — much to the frustration of the command’s top operations officer.

“I’m tired of the excuses. … I’m not even interested to hear how hard it is anymore. It has to happen,” Maj. Gen. David Miller, SPACECOM’s director of operations, training and force development, said Wednesday.

What SPACECOM desperately needs is, in essence, access to an orbital map the emulates today’s widely available interactive maps of the real-time whereabouts of ships at sea, he told reporters in the margins of the Mitchell Institute’s Spacepower Security Forum.

Just like operators in other domains, space operators require a battle management, command, control, and communications (BMC3) system that can provide “targeting-quality predictions for where [something] will be in five minutes, to hand it off to somebody to do something about it,” Milller said.

But right now, it’s not a capability the Space Force can match in the heavens. Rather, surveillance depending mostly on ground-based radars and telescopes offers brief glimpses of space objects’ flight from which computational models can extrapolate predicted paths. But Miller said he needs much better positioning information, much faster. Further, he said, commanders need artificial intelligence/machine learning “decision support” tools to aid commanders in sorting through incoming data.

One key reason that such a BMC3 capability doesn’t exist is the continuing inability of Space Force’s outdated computer systems to integrate data from myriad sources of space monitoring data, including from commercial firms, Miller explained. This is despite decades-long efforts, such as the ill-fated, billion dollar Joint Mission System program, to upgrade space situational awareness information technology, he added.

“Somebody’s got to figure this out. The American people have paid for this. Somebody’s got to deliver,” he said.

That said, Miller noted that he is heartened by the fact the head of the Space Force’s primary acquisition command, Gen. Michael Guetlein, has the issue at the “top” of his mind and is working his staff hard to get capabilities to the field. Space Systems Command (SSC), he noted, is now focusing on rolling out improved capabilities over time via spiral development.

“They’ve said, ‘We’re not going to let the perfect be the enemy of the good anymore,'” Miller said.

SSC’s Space Command and Control (Space C2) program, nicknamed Kobayashi Maru after the Star Trek franchise’s fictional cadet training simulation without a solution, is in charge of those efforts.

Keeping ‘Custody’ Also Requires New Sensors

In his on-stage remarks during the Mitchell forum, Miller explained that SPACECOM’s central concern is the current inability to keep “custody” of adversary satellites and spacecraft on orbit — that is, to be able follow something in real time and know where it is at at any one time. This gap is all the more worrisome, he explained, because adversaries (read: Russia and China) are building on-orbit counterspace systems that can maneuver — meaning extrapolation won’t cut it.

“We do not have the level of custody we need in order to provide a level of accuracy associated with … indications and warning, threat determination, hostile intent and then, ultimately if needed, the ability to target,” he said.

Miller explained that, aside from the BMC3 woes, another foundational problem for maintaining custody of space objects is that there are not enough tracking sensors, either on the ground or in space.

The ground-based optical telescopes and radar making up the bulk of the Defense Department’s Space Surveillance Network were built largely during the Cold War to track incoming Soviet missiles and thus do not provide adequate coverage of the Southern Hemisphere.

“If my primary sensors are largely drawn from radar … around the continental United States, think about how much of the world doesn’t have [coverage],” Miller said.

Further, neither ground-based radar and telescopes, due to the laws of physics, can “see” satellites 24/7. And even when data from those sensors are fused, there still is downtime when any given space object is out of view.

Thus, the information on space object whereabouts now provided to operators, Miller explained, “is based off of observations in the past to predict likely orbital destination in the future” via mathematical models — predictions that have uncertainties baked in “because a lot can happen” in between when something was last seen.

This is the reason SPACECOM is anxiously awaiting the development of new space-based sensors that can keep better tabs on maneuvering satellites and spacecraft, he noted.

Currently, the Space Force has only one such neighborhood watch constellation, the six-satellite Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Program (GSSAP). But it has limited capabilities to stay up close and personal with maneuvering spacecraft.

Space Force Investment

Lt. Gen. Phillip Garrant, Space Force’s head of strategy and resource planning, told the Mitchell Institute in an online session today that filling space tracking gaps is a “critical part of our budget investment” in fiscal 2024.

The service is investing “over $100 million” in FY24 “towards space situational awareness, and the next step, space domain awareness, where we’re not just tracking and [keeping] custody, but characterizing … anticipated behavior,” he said.

Garrant said this includes funds for the Deep Space Advanced Radar Capability (DARC), aimed at improving the ability to track satellites and dangerous space junk in geosynchronous orbit at the outer edge of Earth’s orbit — including in the bright daytime when satellites usually elude radar. The end goal of the program is to host facilities at three sites: one in the Indo-Pacific, one in Europe and one in the United States.

“DARC is a program that we’re looking to work with our international partners on to put deep space radars in other parts of the world. Same thing with the ground-based optical telescopes, again, working with our international partners to really get after the access,” Garrant said.

As for space-based sensors, Garrant pointed to the classified Silent Barker satellite that the Space Force is developing in tandem with the National Reconnaissance Office as one new space tracking capability.

“So, the [FY24] budget does show a considerable investment in all the orbital regimes in all parts of the globe, to get after the concern that [Miller] has with custody in all of his areas of interest,” he said.