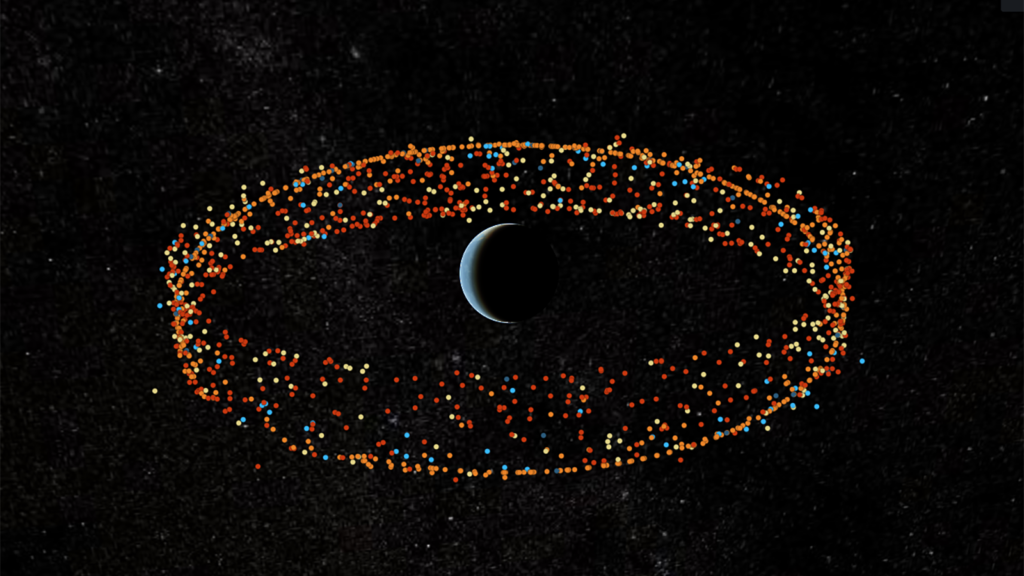

The Satellite Dashboard is an example of an open source tool to monitor close approaches of satellites and debris in space, produced by the Center for Strategic and International Security, the Secure World Foundation, and the University of Texas at Austin. (Satellite Dashboard)

WASHINGTON — The Commerce Department is wrestling with a handful of tough issues as it works to flesh out a framework for a future US space traffic management regime, stemming in large part from the “tripling of active spacecraft in orbit” in recent years, according to the senior official responsible for commercial space.

Richard DalBello, director of the Office of Space Commerce (OSC), last week told the National Space Council’s User Advisory Group (UAG) his office faces five key challenges that he is hopeful the group’s members can help resolve. The UAG had its introductory meeting on Feb. 23, and members also met with Vice President Kamala Harris, who chairs the National Space Council.

“So, at the risk of turning this into a therapy session about me, I’d like to talk about the things that keep me up at night,” he said.

1) SSA Technology Shortfalls

DalBello explained that the most immediate issue is related to the Commerce Department’s long-planned takeover of the Pentagon’s space situation awareness (SSA) responsibilities — which involve tracking satellites and dangerous space junk, and providing warnings of potential on-orbit collisions — to non-military operators. OSC is leading that effort.

“The first challenge is purely technical. There’s just some fundamental things that we don’t do very well,” he said. “Today, SSA is pretty good. It’s not uniformly excellent. This means that the government is sending out a lot of warnings to industry that get ignored,” he explained. “We need to be able to speak with the same confidence in SSA that we speak with air traffic control. And we’re a long way from that … it’s a journey we need to take.”

A related issue is the fact that current technology for cleaning up space pollution is embryonic, he noted.

“Truthfully, there are no great ideas today on how to solve overall the debris problem that we have with large debris and small debris. That doesn’t mean we should stop trying, and there are a lot of great initiatives underway,” DalBello said. “But … if somebody made a major mess in space, we don’t have any way to clean it up. And so, again, we’re at the beginning of a long technical journey.”

2) International Woes

“The second anxiety point that I have is purely international,” he explained, relating to both relations with China and Europe.

“China is a major space player and will be a major space player. They are not participating in the global dialogue, and in global information sharing on SSA. That’s unsustainable,” DalBello said. “The current way of communicating with China, which is by email and the occasionally tersely written démarche, is comically insufficient. And so, major problem.”

He noted that just as no Chinese airliner could land at New York’s JFK airport without communicating directly with US air traffic control, the US “has to find a path forward” for communicating with Beijing on space traffic control.

As for Europe, DalBello explained that the European Union is now more seriously pressing forward with its own SSA system that could work very differently from the hardware and software solutions already developed by the Defense Department and US commercial industry — the existing system which Commerce intends to build upon.

The EU Space Surveillance and Tracking (SST) initiative was started in 2014, with the backing of seven member states who subsequently worked with the European Union Satellite Center to develop data-sharing capabilities. In November 2022, 15 European nations signed a “SST Partnership” accord to more speedily build improved capabilities: original consortium members France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain have been joined by Austria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Latvia, the Netherlands and Sweden.

“The Europeans are standing up a separate SSA system. I suspect we’ll see many other countries do the same,” DalBello said. “So, we’re going to live in a world where you as satellite operator probably will have two or three or four different choices. From our perspective, that’s slightly terrifying to me.”

The problem is that under that scenario there will be “different sensors, with different biases and running on different analytics, producing different results, and I don’t know how to compare any of that yet. That is a technical challenge, but also a political challenge,” DalBello elaborated. “I acknowledge the right of other nations do what they want to have an SSA system. … But we also have a responsibility to figure out how we’re going to talk to each other to make this make sense.”

3) Doing No (Economic) Harm

“Challenge three is a commercial business and policy challenge,” DalBello said. “We’ve been asked to to implement an SSA system, but because the current system isn’t meeting all the needs of the commercial sector we have a whole commercial industry that’s that’s sprung up and is providing additional services. And so part of the challenge for the Department of Commerce is: ‘how do we come into this marketplace and not disrupt it entirely?’ Because when the government enters the marketplace, as the principal buyer, we have a hugely disruptive impact.”

DalBello said that on that front, OSC is trying “to be as open and transparent” as it can, pointing to its January request for information to industry laying out its draft plan to create what is currently called “a basic service” for SSA, which would serve as a foundation that commercial SSA providers could augment for a price.

4) Regulations: Who, What, How

Commerce’s fourth challenge, DalBello said, is a part of an interagency policy question that the National Space Council itself is currently grappling with: figuring out how to regulate “non-traditional” activities in space emerging from the commercial sector — and more controversially, sorting which agency or agencies should do so.

Under current law, the Transportation Department oversees the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) that regulates launch and landing of spacecraft with an eye towards the safety of people on the ground, as well as for aircraft. Commerce oversees the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) that licenses commercial remote sensing firms. And the independent Federal Communications Commission licenses use of the radio frequency spectrum, which all satellites use.

But a number of US firms are pursuing types of activities on space — including a number of things of interest to the Defense Department, such as on-orbit servicing — that today fall through the regulatory cracks.

“We have a lot of new activities — refueling and manufacturing in space, commercial [low Earth orbit] stations, mining on the Moon — we have a bunch of stuff coming at us [that] we’re not really yet poised to, the regulatory regime isn’t really set up to, handle,” DalBello said.

5) Operator Responsibility: Do The Right Thing

The fifth and final challenge, DalBello said, is for government to figure out what the responsibilities of commercial space operators need to be.

“We need to work on the development of, as I call it, a concept of ‘operator responsibility,'” he said. “We are slowly moving out on things like safety, debris mitigation, adherence to best management manufacturing practices, the overall rubric of sustainability. … but we really haven’t had a whole of government, really deep think about how where we want to go on this.”

Specifically with regard to space traffic management, DalBello added, “it’s a little bit alarming to learn that not all operators know where their stuff is.”

The fact that not all operators are as competent as they should be is something that needs to be addressed, he explained.

“I think we’re coming to the point now in our history where perhaps throwing CubeSats into space, that don’t have any propulsion or guidance or way of communicating effectively, maybe that deserves some rethinking,” DalBello said.