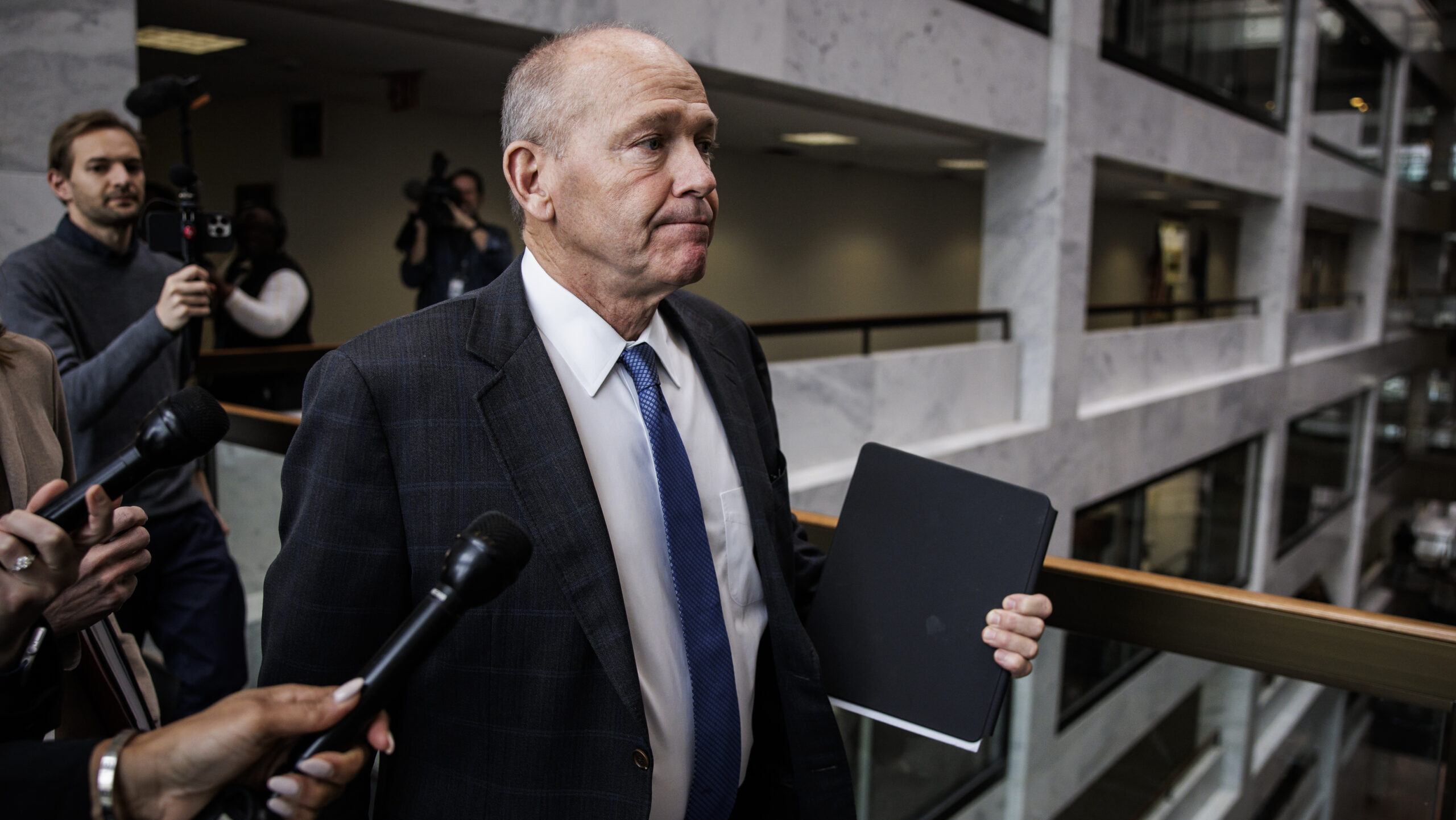

Army officers inspect one small portion of the massive logistics base at Camp Arifjan in Kuwait.

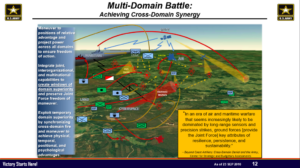

A grim vision of future battlefields has the Army urgently exploring every option to streamline its logistics, everything from cargo drones to “compact fusion reactors.” Moving iron mountains of supplies has been a signature strength of the US military since the Civil War. But against an adversary with precision weapons, those sprawling supply dumps, the long convoys that venture out from them, and the large units that live off them are just big targets. In a future Multi-Domain Battle, the Army wants to fight in small units that can disperse, hide, and keep on the move. That’s not possible while tethered to traditional supply lines. So what the Army calls “demand reduction” isn’t a nice-to-have administrative efficiency, it’s a battlefield necessity.

That’s why the Army: held a “Demand Reduction Summit” in April; will issue a new logistics strategy this year; and is holding major field experiments both now and in 2018. There are a lot of intriguing technologies to look at, especially in robotics. There’s also a fundamental problem. The lion’s share of battlefield demand is the fuel consumption of heavy weapons, like the M1 Abrams tank with its three-gallon-to-the-mile turbine, and the Army doesn’t have the money to replace them for decades.

That’s why the Army: held a “Demand Reduction Summit” in April; will issue a new logistics strategy this year; and is holding major field experiments both now and in 2018. There are a lot of intriguing technologies to look at, especially in robotics. There’s also a fundamental problem. The lion’s share of battlefield demand is the fuel consumption of heavy weapons, like the M1 Abrams tank with its three-gallon-to-the-mile turbine, and the Army doesn’t have the money to replace them for decades.

“The M1… that’s the primary driver of demand in an armored brigade combat team,” Col. Mark Simerly, chief of capability development and integration at the Army’s logistics center, said. “Certainly, the designers of the future combat vehicle understand the vulnerability” and are exploring solutions, he told reporters Tuesday.

The cancelled Future Combat System and Ground Combat Vehicle programs explored hybrid-electric tanks. The Army’s Tank-Automotive center, TARDEC, has built a prototype hydrogen fuel cell car. (Fusion reactors, compact or otherwise, remain science fiction). Ultimately the Army does want to replace the M1, the M2 Bradley, and the M109 Paladin howitzer with vehicles that are more lethal, more mobile, and less fuel hungry — but there’s no funding even to start building new designs until the 2030s.

M1 tanks burn three gallons to the mile and are normally moved long distances by rail.

Everybody’s Effort

So what is the Army looking at to streamline logistics in the nearer term?

Perhaps the lowest-hanging fruit is electronics. Better electrical power management at forward bases and field command posts — software that cycles generators on and off depending on demand, for example — can reduce both heat generated, which shows up on enemy sensors, and fuel consumed. On a larger scale, moving fuel more efficiently to forward units can reduce both the number of vulnerable tanker truck convoys and the frequency with which troops have to stop to gas up again. That’s the idea behind the Automated Fuel Management System, which would transmit information on how long a given unit could keep operating on its current fuel supplies and what resupply was available where. Of course, all such efficiency initiatives rely on relaying accurate data over networks — the first thing an enemy like Russia might attack.

The greatest vulnerability of the logistics system, however, is not its digital networks but the human beings who have to move the supplies around. Some of the heaviest casualties in the 2003 capture of Baghdad came when unarmored, flammable fuel trucks pushed through to the forward-most tanks, and fuel convoys suffered heavy casualties to roadside bombs in Iraq and Afghanistan thereafter.

The unmanned TerraMax M-ATV with its mine roller.

No wonder, then, that the Army wants to minimize the number of soldiers driving supply trucks. An exercise now getting underway at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, is testing so-called “leader-follower” technology, in which ordinary Army trucks are modified to drive themselves, using their sensors to follow a manned vehicle in convoy. The Army is eagerly learning from the commercial sector, but Tesla, Google, and so on aren’t building vehicles to operate off-road, let alone under fire, so the military’s algorithms need to be a bit more robust. The long-term goal is completely autonomous vehicles, said Simerly, but that will require major improvements in artificial intelligence and vision: “Our sensors right now can’t tell the difference between a toddler and a tumbleweed.”

Flying through empty air is actually a lot easier on AI than navigating obstacles on the ground, and it has the added advantage of avoiding roadside bombs and mines — though a sophisticated adversary will have plenty of anti-aircraft weapons. The Army, said Simerly of the Combined Arms Support Command (CASCOM), is looking at three tiers of cargo-carrying unmanned aerial vehicles, all significantly smaller than the unmanned K-MAX helicopter used in Afghanistan:

- a high-end drone capable of carrying 1,500 to 2,000 pounds (less than a third of K-MAX’s payload) up to about 70-90 miles (110 to 150 km);

- a mid-tier drone able to carry 300-500 pounds to resupply, say, a single infantry squad for three to four days; and

- a “micro UAV” able to carry 20-50 pounds from a forward supply point to, say, a wounded soldier needing first aid or a broken-down vehicle needing repair parts.

Ultimately, the Army wants to print spare parts on-site instead of hauling them around, which is why it’s looking very hard at 3D printing. But additive manufacturing still requires raw materials. The Star Trek replicator that makes supplies out of nothing isn’t likely to be a reality in the next few centuries.

Prototype cargo drone, JTAARS (Joint Tactical Autonomous Air Resupply System).

Ultimately, no amount of brilliance by the supply corps will solve the problem by itself. The combat arms that they support — infantry, armor, artillery, aviation — need to figure out new ways of operating and create new units that can operate on Spartan amounts of supply. Addressing the whole problem was the point of the Demand Reduction Summit held April 29. It wasn’t just a meeting of logisticians — from the Army’s Pentagon HQ, Army Materiel Command, and CASCOM: Representatives of the combat arms, as well as Special Operations Command, Forces Command, Army Research Laboratory, the Marines, the Navy, and the Army’s acquisition secretariat all showed up.

“The main goal for the summit was to get the word out about demand reduction and to get everybody’s buy-in that this is not just a sustainment challenge, this is a Total Army challenge,” said Col. Stephanie Gradford, chief of the sustainment division at ARCIC, the Army Capabilities Integration Center. “(It’s) everybody’s effort to try to reduce demand to make our brigade combat teams nigh-independent.”