HUNTSVILLE, ALA.: The robotic war machines of the future are strangely cute. Here at the Association of the US Army winter conference, BAE Systems is showing off a 12-ton robot mini-tank that looks like a baby M1 Abrams. There’s serious lesson here which the Army’s Next Generation Combat Vehicle effort is taking to heart. Automation, by replacing bulky humans with compact electronics, can make for smaller combat vehicles that are not only cheaper and more fuel-efficient, but harder to hit.

“The key to survival on the battlefield is not being seen,” said David Johnson, a leading scholar and former top advisor to the Chief of Army Staff. “If you saw the BAE autonomous tank… it is radically smaller than anything we have now, and smaller for a vehicle on the battlefield is a good thing.”

Russia’s new T-14 Armata tank on parade in Moscow.

You don’t have to replace the entire crew to benefit, either. The Russians have long been obsessed with smaller tanks, to the point of having height limits for tank crewmen, and starting with their T-64 in the 1960s, they replaced the main gun’s human loader with a mechanical one, allowing for a smaller turret. (The M1’s designers didn’t do this because Cold War autoloaders were not only unreliable but slower than a well-trained human). Today, Russia’s new T-14 Armata tank has a completely automated turret, with the entire three-man crew in the heavily armored hull. The US Army tried a similar configuration with its cancelled Future Combat Systems, a program to build much lighter armored vehicles. BAE’s Armed Robotic Combat Vehicle mini-tank was also originally built for FCS.

Smaller vehicles have advantages for mobility as well as for survivability: They’re easier to transport to the battlefield by ship, plane, or rail, and they’re easier to keep supplied. That’s in stark contrast to the M1 Abrams, which for all its virtues gets three gallons to the mile. During the seizure of Baghdad in 2003, some M1s had to shut down their engines until a fuel convoy could push through, taking casualties on the way. The Army’s concepts for future Multi-Domain Battle envision widely dispersed units, constantly on the move to evade detection and destruction, and able to live off infrequent resupply — something that would be difficult for current heavy forces.

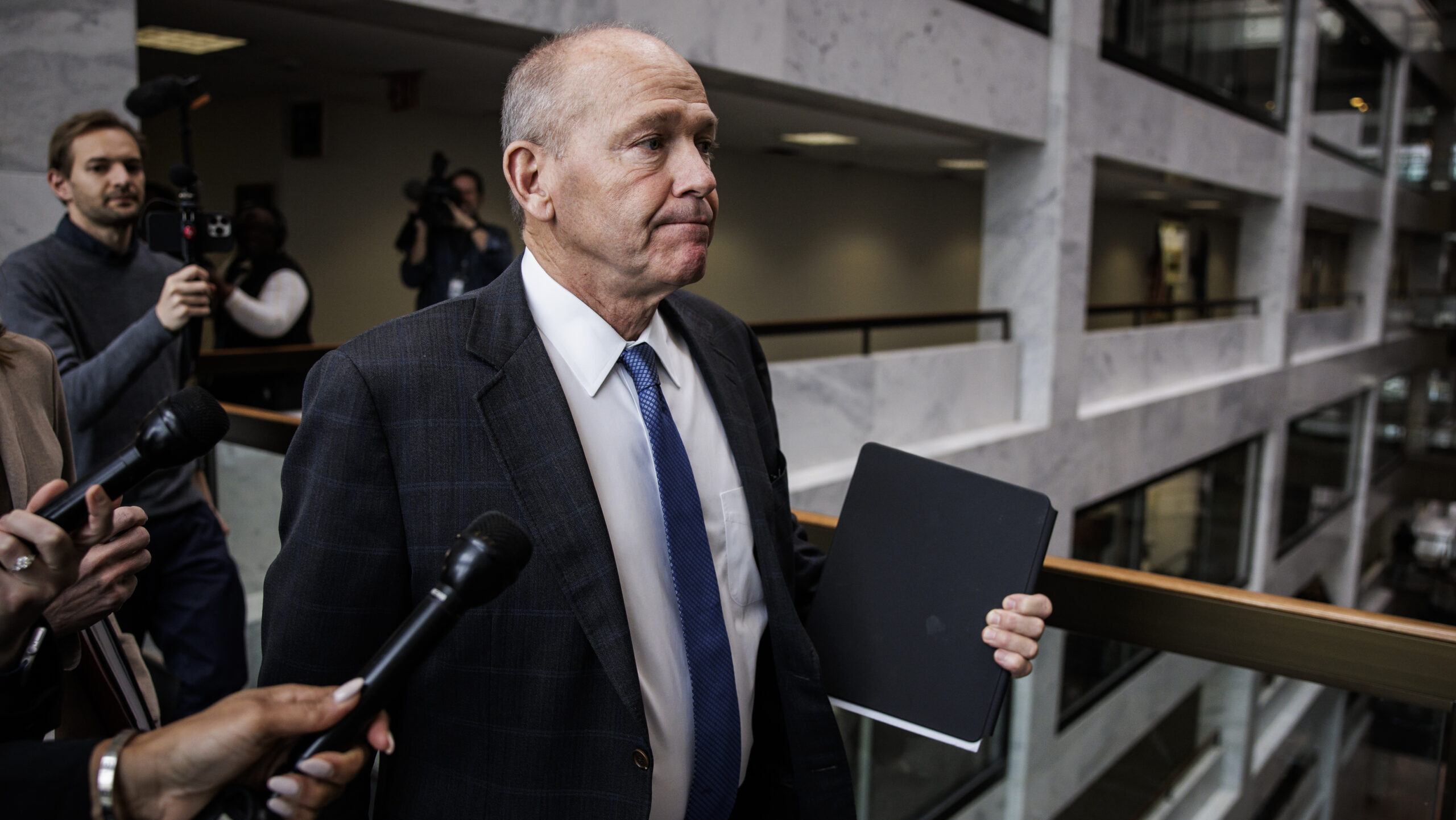

David Johnson (left) and Col. William Nuckols (right) talk at AUSA Global in Huntsville.

The Next Generation Combat Vehicle, set to enter service by 2035, would be designed to carry out those concepts, said Col. William Nuckols, director of mounted (i.e. vehicle) requirements at Fort Benning’s Maneuver Center. “This is not just about a vehicle, this is about a concept and a formation,” he said at AUSA, “the formation that we need to be able to fight the way that’s prescribed in the Army Functional Concept for Movement and Maneuver.”

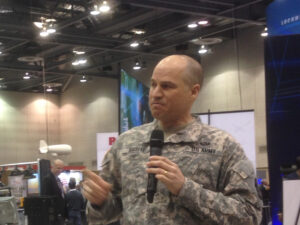

“Many of the things in the Movement and Maneuver concept do a great job of making the case for new-start combat platforms that make different trade-offs,” said Maj. Gen. David Bassett, Program Executive Officer for Ground Combat Systems. For instance, the Army has upgraded the M1 and M2 engines, he told me at the conference, and there’s more promising tech in the works — but the engine compartments on those vehicles will stay the same size they were when designed in the 1970s, putting a strict physical limit on what upgrades are possible. If you want to dramatically change fuel consumption, speed, firepower, or any other performance characteristic, you need to design a new vehicle.

Maj. Gen. David Bassett

So how do you build a vehicle to burn less fuel? “Fuel consumption is driven in no small way by overall vehicle weight,” Bassett said. Weight, in turn, is mainly driven by armor. Since no one’s about to develop any new magical armor material that lets us get the same protection for less weight, if you want to reduce weight, you have two choices: accept less protection — fine with unmanned vehicles, not so with humans at risk — or shrink the “volume under armor” you have to protect. Shrinking volume also makes the vehicle a smaller target.

“We are certainly keeping our aperture wide open” about what size and shape the NGCV could be, Nuckols said. In fact, he said, “we’re not certain” if NGCV will replace the M1 Abrams tank, the M2 Bradley Infantry Fighting vehicle, “or potentially both. It could be a family of vehicles.”

Army troops dismount their M2 Bradleys in a simulated assault.

For a potential Bradley replacement, Nuckols said, the Army is studying both reducing the crew and reducing the number of infantry passengers. The Bradley today has a three-man crew: a driver in the hull, a commander and a gunner in the turret (its 25 mm ammunition is small enough it doesn’t need a dedicated loader). The commander’s role is to keep a 360 lookout for threats, targets, and terrain so he can direct the gunner and driver, who focus more narrowly on a given target or path. With enough assistance from sensors and artificial intelligence, however — for example, Nuckols said, “automated target acquisition” to serve as a virtual gunner — you could get down to two crew. You could also put both of them in the hull, which would allow for a smaller, cheaper turret that’s harder to hit and, if it is hit, the likely ammunition explosion doesn’t kill anyone.

To really reduce the size of the hull, however, you need to make peace with carrying fewer infantrymen. That’s painful because the raison d’être of an Infantry Fighting Vehicle is to carry infantry. The Bradley nominally carries seven, but that was with the smaller equipment loads — and smaller soldiers — of the 1980s, and even then one man had to cram into the charmingly named “hell hole.” In practice, Bradleys today manage from four to six depending on the mission.

The Army’s standard infantry squad, however, is nine men, a number the service’s analysts and tacticians swear by. The eight-wheel-drive Stryker can carry a full squad, but it’s both large and lightly armored. The cancelled Ground Combat Vehicle would also have carried nine, but putting heavy armor around that many men — plus a manned turret — pushed the vehicle’s weight north of 60 tons. So, while the Army won’t give up the nine-man squad, it’s considering splitting that squad between two (or even three) smaller vehicles.

BAE’s Armed Robotic Combat Vehicle (ARCV)

However big they are, the manned Next Gen Combat Vehicles could well operate with completely robotic “wingmen” similar to BAE’s mini-tank, which is designed to keep up with full-sized armored vehicles. The autonomy software would have to improve. Currently, the BAE Armed Robotic Combat Vehicle can navigate from waypoint to waypoint, using its LIDAR sensors and object recognition to avoid hitting obstacles and running people over, BAE’s Jim Miller told me. For precise driving, like bringing it into the AUSA exhibit space, however, a human takes over by remote control. A human also has to remote-control the gun — no Terminators here. In fact, the ARCV’s robot brain currently doesn’t have the capacity to realize it’s under attack.

Given rapid advances in automation, however, those should be solvable problems. The Army is very interested in autonomous vehicles that could scout ahead of the manned machines or provide supporting fire alongside them. Ideally, these machines wouldn’t require one human remote operator per unmanned vehicle, but would be smart enough that a single human could supervise a whole pack of robots.

The question of control is critical. “One of the problems we have with robotics right now, Sydney, is the fact that we can’t have assured control,” Nuckols said. “Until we have that assured control… we’re going to be hesitant to replace any of our current formation capabilities with a robotic platform.”

If that’s solved, however, it opens up some radical possibilities. “There’s no guarantee that the Abrams will be replaced by a future tank,” Nuckols said. “It could conceptually be replaced by an autonomous vehicle with the lethality of an Abrams.” Equally lethal, but probably smaller — and perhaps cuter.