https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yOl_JOesU54

The first Marines to hit the beach in future wars may well be robots. Flying, swimming, rolling and swarming, the unmanned advance guard will scout out enemy positions, neutralize mines and send out decoy transmissions to deceive the enemy. Then the humans will start to come ashore. First handfuls of SEALs and Marine Force Recon scouts, then long-range raiding teams launched from ships 100 miles out, and finally large landing forces in amphibious combat vehicles — followed by more unmanned craft carrying supplies.

This future Marine Corps force may never get the high-speed water-skiing tanks once envisioned. Marine leaders and experts are clearly less interested in any single high-cost system, however high-performing, than in the combined effect of a host of more modest technologies — technologies they can get more affordably and faster.

“The commandant wants us to go faster. The Hill wants us to go faster. Everyone wants us to go faster…with our acquisition process (and) rapid prototyping,” Lt. Gen. Robert Walsh, deputy Commandant for combat development, said in a phone call with reporters yesterday. “The pressure to go faster because the threat is driving us to go faster.”

Lt. Gen. Robert Walsh

That’s the imperative driving the cumbersomely named Ship to Shore Maneuver Exploration and Experimentation Task Force (S2ME2 TF). Set up in late August, the task force sent out a special notice to industry and academe on October 7, inviting all comers to demonstrate technologies for future amphibious warfare. There’ll be an industry-government workshop in November, the Marines will choose technologies in December, and wargames testing the tech will start in April 2017 at Camp Pendleton.

Walsh’s chief co-conspirator on S2ME2, John Burrow — assistant Secretary for the Navy for research, development, test and evaluation — says the plan is to bypass the laborious requirements and procurement process, instead getting combat troops and industry techs together in the field to exchange ideas early and field new gear “as fast as we possibly can.”

So the Marines’ focus is on “non-developmental” items that don’t require years of work to work, Walsh said. “Gen. Neller would rather have the 80 percent solution — he says this all the time — and have it now than take five years, 10 years” developing the perfect thing.

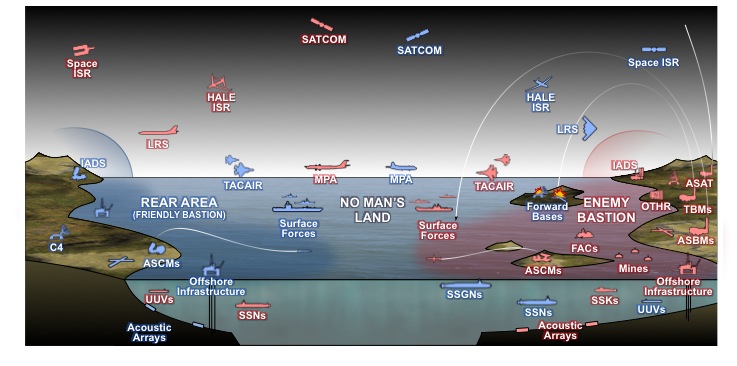

What does Walsh want? The problem the Marine Corps wants to solve is the global spread of long-range smart weapons — and the sensors and networks required to target them — backed by advanced aircraft, submarines, drones, hacking, and jamming. Such Anti-Access/Area Denial systems (A2/AD) could slaughter US forces approaching the beach in traditional formations. But the Marines also don’t want to just sit on their ships and hope that Air Force and Navy airstrikes will eventually wear down the defenses from long range.

The first solution proposed to A2/AD was “rollback,” said Doug King, director of the Ellis Group at the Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory: “I stay at a distance until I roll back (the A2/AD danger zone) and then I can close, closer and closer.” But with adversaries fielding ever-longer-ranged weapons — including unconventional ones like terrorists and hackers that can hit the US homeland — the safe distance gets more and more distant, King told me, and rollback becomes gets more and more impractical. At some point, you have to stop searching for a safe zone to start from and accept you’re going to have to operate “in the contested space” — the danger zone.

CSBA graphic

In other words, rather than hanging back, the Marines want to press forward under the guns (and missiles and radars and jammers) of the enemy. This is something all the services are increasingly exploring, from the Army’s Multi-Domain Battle to the Navy’s Electromagnetic Spectrum Warfare and the Air Force’s stealthy, long-range B-21 bomber. The goal is to slip through the cracks of the defense — and anything as complex as A2/AD is going to have weak points — and then force those cracks to open wider until the entire system falls apart.

The principles are ancient. Sun Tzu likening an army to water, flowing wherever resistance is weakest. Liddell Hart described attacks as an “expanding torrent.” The Germans invented stormtroop infiltration tactics in 1916 and married it to tanks and aircraft and radio to make the blitzkrieg of 1939. But the technologies and their tactical application are new.

German PzKpfw IV in France, 1940

“We’ve also put some thought into the analogy to World War I, World War II, defense in depth, and German techniques for penetrating that and creating gaps that they can push a larger exploitation force through, and that’s where we would like to go with 21st century maneuver warfare,” said Marine Lt. Col. Edmund Clayton, a member of King’s Ellis Group. “(But) in the 21st century we’ve got the electromagnetic spectrum as a domain we have to deal with; there’s cyber, there’s space.”

Those new dimensions create dangers, but also opportunities — and the latter is where the S2ME2 experiments come in. “Maneuvering in the information spectrum, maneuvering in the cyber spectrum” open new avenues for attack alongside land, air, and sea, said Walsh. The ultimate goal is to “own the electromagnetic spectrum,” he said, just as the US “owned the night” when it had the lead in night vision and the tactics to use them.

For example, the Navy is already kitting out in-service small craft with robotic controls and developing unmanned vessels to hunt mines. “What if we put sensors on board,” Walsh suggested, “using the same existing boat that the Navy’s developing already,” that let it do double duty as an advance scout for a Marine Corps landing force? What if you equipped it to scan for enemy transmissions — or even emit decoy signals of its own, making a single robotic boat appear over the air waves as a Marine assault force?

Robots could also have a physical impact, clearing mines and obstacles from the shallows and the landing beach, Walsh said, much as frogmen cleared the way at Iwo Jima. Robots are already essential to US bomb squads on land, he noted, so why not in the water? You could even have unmanned boats land unmanned ground vehicles with remote-controlled weapons: Imagine replaying first 30 minutes of Saving Private Ryan, the bloody frontal assault on a defended beach, without a single human being dying.

The Marines are also working with the Army to develop robotic supply trucks, exploiting self-driving technology being developed by the likes of Google and Tesla. The two services are also both intensely interested in countering enemy drones, shooting or zapping them out of the sky with lasers, jammers, and hacking.

BAE Systems Amphibious Combat Vehicle

What’s unique to the Marines, however — and uniquely challenging to develop– is armored vehicles that can swim from ship to shore. Trying to replace their 1970s-vintage Amphibious Assault Vehicle (AAV), the Marines spent years struggling to develop the 20-knot Expeditionary Fighting Vehicle before settling for the six-knot Amphibious Combat Vehicle AACV) instead. The EFV was supposed to cross large stretches of water at high speed, letting Navy ships launch it from outside the range of shore-based anti-ship missiles. But missile ranges kept getting longer, while making the EFV move fast on water made it too costly, complicated, and unsuited for combat on land.

“(We’re) looking at other ways to get Marines ashore faster at longer distances,” Walsh said. “We’ve looked at capabilities of putting ACVs or AAVs onto an LCAC (hovercraft) or something like that that could bring them in closer at higher speed and then drop them off.”

What’s more, with the new focus on pushing into the A2/AD danger zone, the Marines have moved away from the whole idea of stand-off the EFV was meant to support. While the Marines still plan to launch hit-and-run raids from 100 miles offshore, Walsh said, they accept they’ll have to fight their way in closer — with Navy and joint help — before launching a full-scale landing force. In this kind of battle, a first wave of robots could take a lot of bullets for the Marines.