B-52 heavy bombers arrive in Qatar to join the air war against Daesh.

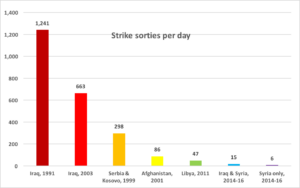

CORRECTED strikes per day figure WASHINGTON: The air war against the Islamic State is not “anemic,” a Central Command spokesman told Breaking Defense, rebutting a critique of the campaign we published last week. To say the rate of airstrikes in Syria and Iraq is less than against Iraq in 1991 and 2003, Serbia and Kosovo in 1999, or even Libya in 2011 is missing the point, CENTCOM’s spokesman told us.

Danish fighters refuel from a US tanker over Iraq.

“We’re not fighting the last war, we’re fighting this one,” said Lt. Col. Chris Karns, director of public affairs for Air Forces Central Command (AFCENT). “While the numbers may not compare to other wars, they don’t need to compare. The weapons of today are more precise and the expectations to limit civilian casualties are much greater. The most relevant measure of effectiveness is not the number of strikes, necessarily, but the effect one is having on the enemy’s ability to wage war,” Karns told us in an exchange of emails.

Using the derogatory Arabic acronym for the self-proclaimed Islamic State, he said that, “Da’esh has lost about 50 percent of the territory it once held in Iraq. Their territorial loss in Syria is about 20 percent. It is reported that Daesh’s oil production has been reduced by more than 30 percent, with oil revenue down by as much as 50 percent.”

“The numbers (of strikes) and pressure being applied to Da’esh has been consistent and persistent since July 2015, with noteworthy effects,” Karns said, rebutting the critical comments by David Deptula, a retired Air Force three-star and a key planner of the 1991 Gulf War, in our story about the air war.

Yes, the number of airstrikes in Syria and Iraq is lower than many past campaigns, Karns acknowledged. But today’s weapons are more precise, and today’s rules of engagement are more stringent, factors which reduce number of weapons released without necessarily reducing the campaign’s effect.

“The fact is today we’re hitting more lucrative targets while having increased success, placing stress on the enemy and impacting their decision-making,” Karns said. “Sheer numbers do not necessarily translate into operational success.”

Data courtesy David Deptula, Mitchell Institute

That said, Karns took care to counter the numbers provided Breaking Defense by General Deptula. Deptula’s analysis of official CENTCOM data showed 15 US airstrikes a day, on average, since the beginning of the air war in August 2014: nine strikes a day in Iraq, less than half of them — just six — in Syria. Karns counted 13 US Air Force airstrikes a day, again with six hitting targets in Syria. Adding strikes by other US services (principally Navy) brings the daily total to 18, and, “when you look at the coalition as a whole,” he said, the average jumps to 20 strikes a day.

There are almost twice as many sorties — almost 40 a day — where planes fly out loaded with munitions but don’t strike a target, Karns’ figures show. That’s a necessary inefficiency for a campaign that takes great care not to kill civilians and an enemy that takes care to hide among them. “(It) reflects the discipline and exacting standards being applied to targeting and strikes,” Karns told us. “Employing all the munitions on an aircraft is not a meaningful metric, especially in a war where the enemy wraps itself around the populace whenever it gets the chance to do so.”

Then there are hundreds of sorties that don’t go out armed at all, but make crucial contributions, for example by providing intelligence for both future airstrikes and for Iraqi operations on the ground.

“The coalition typically flies in excess of 150 sorties a day (and) it is much broader than strike missions,” Karns said. “The ISR (intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) piece is also critically important….When an enemy is wrapped around a population, the intelligence piece is crucial and sets the conditions for strikes.”

F-15E Strike Eagles return from the first strikes on Islamic State targets in Syria, 2014.

Deptula Replies

We gave General Deptula a chance to comment on CENTCOM’s emails. He agreed “wholeheartedly” with Karns that counting airstrikes matters less than measuring effects, that outputs matter more than inputs. Those are all fine principles, but he doesn’t think CENTCOM is practicing them — primarily because the Army, not the Air Force, is running the war.

David Deptula

“Where is the description of the strategy of the campaign, and the operational level objectives for which precision force is being applied to achieve?” Deptula asked. CENTCOM’s own statistics “only identify and list sorties, weapons released, and pounds of cargo delivered. There is no identification of specific effect objectives, or the associated measures of merit toward accomplishing those objectives.”

Instead, “the approach taken… is essentially the same as that taken in the counterinsurgency operations in Afghanistan for more than a decade,” Deptula said. “It is an approach that is treating the Islamic State as an insurgency and applying counterinsurgency driven rules of engagement (ROE).” As a result, the emphasis is on striking enemy forces that pose a potential threat to our allies on the ground, hitting tactical rather than strategic targets.

But the Islamic State is enough like a state that it can be taken down like one, Deptula argued. The same leadership and organization that made Daesh so effective on the battlefield also make it vulnerable.

“This conflict is against an organization that has all the elements of a state, and it can be negated by rapidly and simultaneously attacking each of them,” Deptula said. Instead of targeting frontline forces, he said, “focus on the opponent’s leadership, decision-making process, and mechanisms of command, control, management, communication, infrastructure, and key essential systems that enable them to exist as a functional organization.”

F-15Es prepare to sortie against ISIL in 2016.

This is all classic airpower doctrine dating back to Billy Mitchell and Giulio Douhet in the 1920s, and there is a century of debate over how well it works in practice. There’s perpetual tension between the Air Force’s desire to strike at the head of the snake — headquarters, war industry, energy infrastructure — and the Army’s desire to strike at the coils currently choking troops on the front line.

The administration needs “to put an airman in charge of the campaign, not the Army,” Deptula said. “The asymmetric advantage airpower brings to the fight has been shackled with unwarranted constraints, and it’s been used as support to ground forces,” mainly in Iraq, instead of striking vital targets in Syria.

One of those “unwarranted constraints” has been the strict rules of engagement, Deptula said. A more intense air campaign would accidentally kill more civilians, he acknowledges. But it’s the only way to stop the Islamic State from intentionally murdering far more.

“Contrary to what many might assume, it is actually perfectly legal to execute an otherwise lawful attack notwithstanding the knowledge that, in fact, civilian casualties will inevitably occur,” Deptula said. “The effort to avoid civilian casualties at any cost actually winds up getting more innocent people killed….The best way to minimize casualties is to conduct a swift, rapid and focused operation to eliminate the Islamic State.”